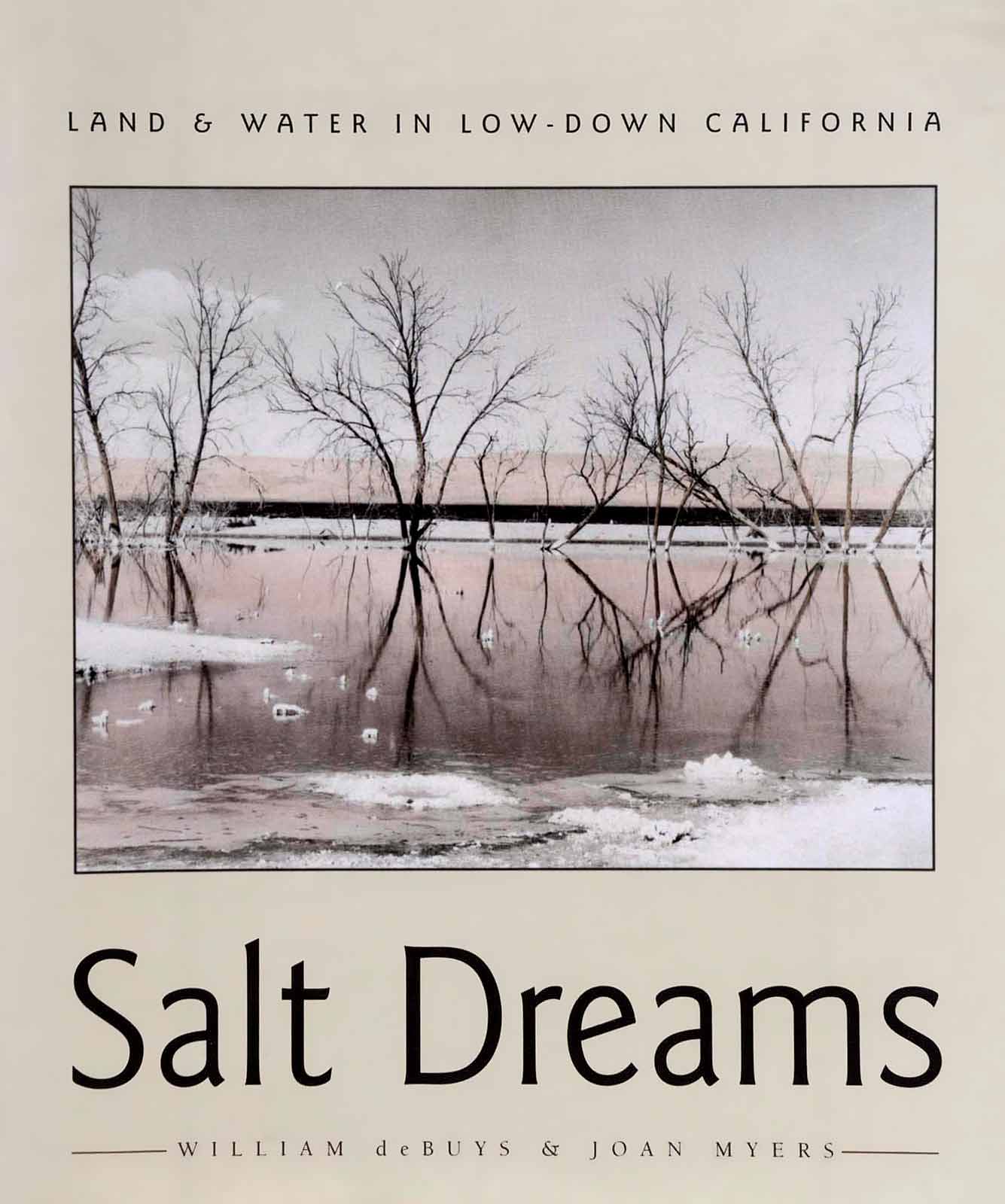

With Joan Myers

• The 1999 Western States Book Award for Creative Non-Fiction• The 1999 Clements Prize for the Best Non-Fiction Book on Southwestern America• The 2000 Norris and Carol Hundley Award from the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association

In low places consequences collect, and in all North America you cannot get much lower than the Imperial Valley of southern California, where one town, 186 feet below sea level, calls itself the Lowest Down City in the Western Hemisphere, and where the waters of the Colorado River sustain a billion-dollar agricultural industry. The consequences of that industry drain from the valley into the accidentally man-made Salton Sea, California’s largest lake and a vital stopping place for migratory waterfowl. Today the Salton Sea is in desperate environmental trouble.

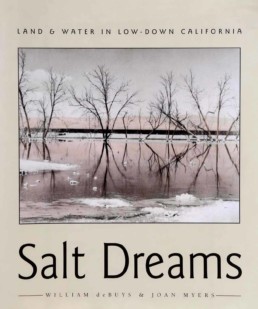

A second river also ends in the Salton Sea. It is a river of dreams, the remains of which may be seen in the failed real estate developments that sprawl beside the sea. As the ending point of both the real Colorado and this river of dreams, the Salton Sea has become emblematic of much of the history of the American West. Its troubling story is masterfully told here in William deBuys’s narrative and Joan Myers’s austerely beautiful photographs.

The story of Southern California is fundamentally a story about the control of nature. Beginning with the Yuman-speaking tribes encountered by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, deBuys traces the subsequent exploration and development of the region through the Gold Rush of 1849, the government-sponsored surveys that followed, and the inept tinkering with the river by an assortment of irrigation and development interests that resulted in the floods that formed the Salton Sea nearly a century ago. He introduces us to a gallery of rogues and dreamers who saw a great future for this arid wilderness but could never refrain from interference with the forces of nature.

The floods that produced the Salton Sea created a vast desert oasis, but the agricultural exploitation of the region, combined with evaporation, poisoned that paradise. The stark beauty of the desert, the engineering feats that have transformed the landscape, and the eerie spectacle of Salton City and its ruined beaches and abandoned yacht club are the subject of Myers’s photographs, made over a period of more than ten years. In the last section of Salt Dreams, deBuys acquaints us with the human and avian denizens of the region, all struggling for survival as the twentieth century draws to a close. The history of chicanery and greed recounted in deBuys’s narrative and his empathy with the desert dwellers he and Myers have come to know hardworking laborers and entrepreneurs who live on both sides of the Mexicali border, eccentrics hiding out in the Salton Desert, pelicans dying of avian botulism are crucial to an understanding of the border issues of today and the impassioned environmental debate on whether and how to save the Salton Sea.